by Robert Montgomery, May 5th 2024

Sam King’s book, Imperialism and the Development Myth: How Rich Countries Dominate in the Twenty-first Century, has three key strengths. Firstly, it repositions Lenin as a central figure in contemporary Marxist discussions on imperialism. Secondly, it updates the ideas of dependency theorists by highlighting the growing gap between imperialist centers and peripheral regions. Lastly, King’s emphasis on the long term appropriation and transfer of surplus value by the imperialist countries from the dominated countries, connects Lenin’s ideas more closely with Marx’s law of value.

King’s book is more than a thesis about imperialism and unequal development; it’s a polemic arguing against the view of a “rising China” leading the BRICS countries into a multipolar world order, strong enough to challenge the hegemony of the US dominated imperial system. The multipolarity school is best represented by the International Manifesto Group headed by the Marxist economist, Radikha Desai. 1

King wants to debunk this perspective, devoting three of his ten chapters to proving that “rising China” is a myth. Later, I will argue that King seriously overshoots the mark on China.

King tells how and why Lenin’s work was buried sometime in the 1980s. Eclectic theories like “beyond imperialism” and “neoliberal globalization” substituted for Marxist analysis. Writing in Beyond the Theory of Imperialism William Robinson epitomized the post-Lenin consensus:

“The classical image of imperialism as a relation of external domination is outdated and must be abandoned, together with notions such as center, periphery, and surplus extraction.”

King attributes the retreat from Lenin to objective factors rather than academic fashions like globalization. The postwar anti-imperialist struggles, and the solidarity movements in support of Cuba, Vietnam, Chile, Africa, and Central America sparked interest in national liberation movements and theories of imperialism. The waning of the anti-imperialist wave punctuated by the defeats of the 70s in Chile, Argentina, and Central America put a brake on further serious engagement with Marxist theories of imperialism.

By the 1980s many demoralized Marxists had drifted so far from Lenin that the “Warren thesis” was taken seriously. It claimed that capitalism was an economically progressive force that was developing the 3rd World, and should be embraced by Marxists. The Warren thesis found a muted echo in Marxists who accepted its economic conclusions while disagreeing with it politically. Alex Callinicos argued that in countries like Brazil, capitalism had opened up, “new centers of accumulation,” and these countries were “sub-imperialist countries”. King stresses the underlying links between Warren, “new imperialism” Marxists like Callinicos and his co-thinker Chris Harman, and postwar bourgeois modernization theories like Rostow’s “stages of economic growth.”

With the eruption of imperialist war in the Mideast and the world financial crisis of 2008, national antagonisms and military conflicts reemerged. These developments brought home once again the need to return to classical Marxist theories of imperialism. If we are to fight imperialism we first must understand it. So in returning us to Lenin, King’s book is a much needed breath of fresh air. Graphs clearly show the G7 richest countries clustered far above the poorest bloc, with a largely empty space in between a small number of countries. Since Russia and China have about 11% GDP per capita of that of the United States they rank in the top tier of the poorest majority of dominated countries. The rich countries are graduated as well, with Spain ranking as the poorest with a GDP per capita at around 45 percent that of the United States.

In a speech to the recent meeting of China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) premier Li Qiang restated the party’s aspiration to become a “moderately developed” economy by 2035. This would bring China to the level of Brazil, Russia,Turkey or Mexico. This is not even at the bottom rung of advanced countries like Belgium or Portugal. King sees China as not even close to the level of economic power needed to mount a serious challenge to US economic hegemony.

The book is particularly strong in its discussion of whether China is an imperialist power. The majority of Marxists consider China imperialist, to the extent of giving different levels of support to the U.S. against it. To his credit King isn’t one of them. As Barry Sheppard writes: “This is dangerous and wrong.” It’s dangerous for the obvious reason that it leads supposed Marxists to align with the imperialist powers as they’ve done over Ukraine. It’s wrong because China is a net exporter of surplus value to the world economy. It does not import surplus value by exporting its own capital to earn higher profit rates exploiting the resources and labor of other dominated countries.

I recommend to those interested in a concise, readable review of the book I recommend reading Barry Sheppard: Imperialism and it Myths.

While King is correct in comparing today’s China to Brazil or Mexico rather than to the US, he’s badly off the mark in three ways:

- seeing China as locked in place within the global division of labor as structured by the logic of monopoly capital

- Claiming China is unable to develop beyond the level of a low value-added export platform for cheap consumer goods manufactured by exploitation of low skill labor of low value added consumer goods for the imperialist countries

- Viewing China as a capitalist state where firms like Foxconn exploit a pool of low-wage labor to produce low value added exports for the imperialist countries.

King views China as a typical midrange capitalist state skimming off a share of the superprofits of mostly foreign owned firms exploiting native Chinese workers producing cheap exports.

“China became the most successful practitioner and developer of the non-monopoly labor processes allocated to the periphery within the imperialist-dominated international division of labor. In other words, China’ success is as the Third World society par excellence. It moved from one of the poorest Third World states to one of the least poor.” (Ch 16)

Using GDP per capita King correctly compares China to Brazil or Mexico rather than to the US, but he overstates the case by seeing China as locked in the periphery of the imperialist dominated global division of the labor process. From the vantage of the long arc of the postwar era, how do the US and China compare in terms of economic dynamism?

The graph of US GDP shows a long term downward trendline in the seventy years between 1950 and 2020. Between 1978 and 2020 the growth curve of US output shows protracted decline, hits bottom after the financial crisis of 2008, and has yet to rebounded since the ‘08 trough.

China expanded massively between 1978 and 2015, while the Western economies were stagnating. In that period China increased its economy by thirty-fold. In 1978, the per capita income in China was less than that of Sub-Saharan Africa. Now, China’s per capita income is at the median level in the world and continuing to go up and it has reduced absolute poverty within its borders. At the same time, China has emerged as the leading industrial power in the world in terms of simply industrial output. 2

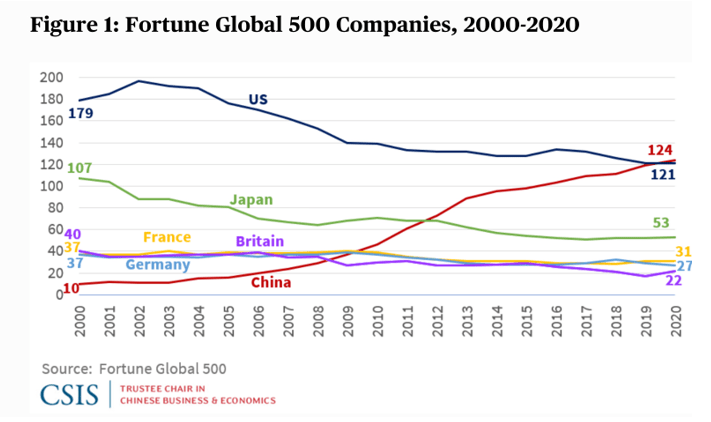

As a modern, urbanized society functioning in the world market China is using the newest cutting edge technology. According to the Fortune Global 500 list of the world’s largest companies, 25 Chinese companies rank in the top 100. For the first time China had the largest number of companies 3represented. Chinese firms slightly outpaced those from the United States,124 to 121. China now has more firms on the list than France, Germany and Great Britain combined. In the last two decades the number of Chinese firms has grown over twelve fold, while the proportion of American firms has fallen by one-third, from 36% to 25%. 4

China is:

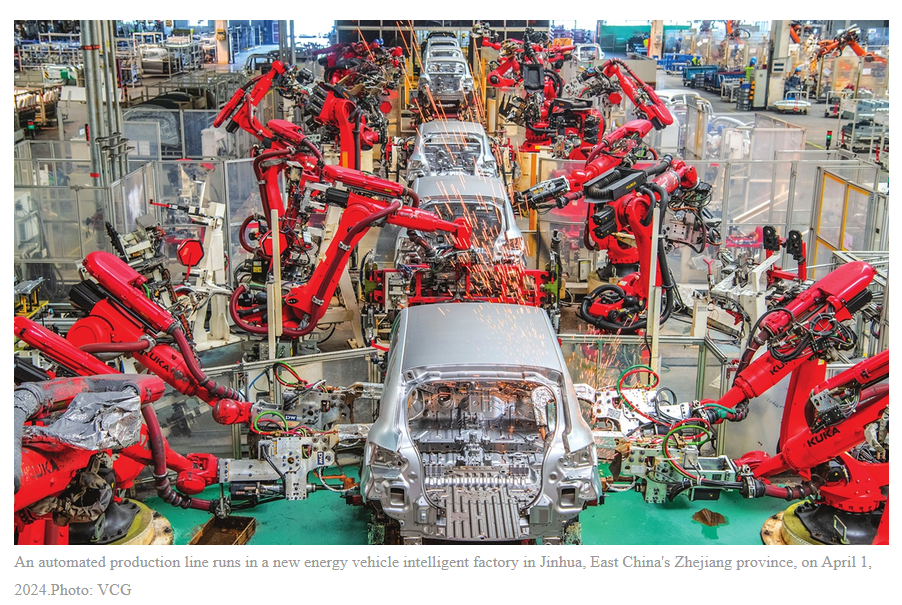

- investing heavily in green technology development. It currently dominates electric vehicle production accounting for more than half of all vehicles, three-quarters of the world’s EV battery production (the battery accounts for about 40 percent of the cost of an electric vehicle), and the minerals necessary to produce them—lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and graphite.

- a major player in the field of robotics, with the Chinese government actively supporting the development and deployment of robotic technologies. China has been investing heavily in robotics research and development, with a focus on both industrial and service robotics. The country has a growing number of robotics companies and is increasingly exporting robotics products to markets around the world.

- developing advanced technologies such as quantum computing, graphene-based chips, and other next-generation technologies. It has made significant investments in research and development, and has a strong focus on advancing its semiconductor industry.

- investing heavily in areas such as artificial intelligence, advanced computing technology and semiconductor manufacturing, positioning itself as a global leader in technological innovation and has a number of leading research institutions, universities, and companies dedicated to developing cutting-edge technologies in electronics and computing.

As of 2021, Chinese smartphone manufacturers like Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo, and Vivo accounted for a significant percentage of 5G smartphones in the world. Estimates suggest that Chinese brands hold around 70-80% of the global market share for 5G smartphones. Huawei, in particular, has been a major player in the 5G smartphone market, although it has faced challenges due to restrictions imposed by the US government.

Chinese firms manufacture 20-30% of all machine tools worldwide, manufacturing a wide range of machine tools, including CNC machines, machining centers, lathes, milling machines, and more. While China produces a variety of machine tools at different levels of sophistication, it is focusing on developing high-precision and advanced machine tools to compete at the international level. Shenyang Machine Tool, Dalian Machine Tool Group, and Jinan No. 1 Machine Tool lead the way in both production and innovation. With investments in research and development, technology acquisition, and skilled workforce, China is becoming a major player in the global machine tool industry. The Chinese government has supported the growth of the machine tool industry as part of its efforts to promote manufacturing and industrial development.

One of King’s most egregious oversights is his treatment of Chinese R & D (pp 222-225). He relies on a single source, the American China specialist Edward Steinfeld, to deny that Chinese firms conduct significant R & D of their own: “MNCs (multinational corporations) have been able to dominate the R & D scene in China.” To the extent that Chinese firms do any R & D at all it’s in the low end export sector. According to King, “Independent R & D led by Chinese capital typically involves reverse engineering of existing products developed overseas like Japanese motorcycles.” Edward Steinfeld is a Director of the National Committee on United States-China Relations, founded by academic and corporate “China Watchers”.

Backward Technological level?

King insists that China lacks the scientific resource base needed to break away from having to import the most advanced technology from the imperialist centers in order to become a technological innovator in its own right. However, Renauld Bertrand writes:

“China has become an innovation powerhouse. In 2023 it filed roughly as many patents as the rest of the world combined and it’s now estimated to lead 37 out of the 44 critical technologies for the future. All this too has implications when it comes to the final prices of its products.”5

As shown in the graph below China led the top 10 countries in filing new invention patents in 2020, almost two and a half times as many as the US, and increased its filings by a record 6.9%.

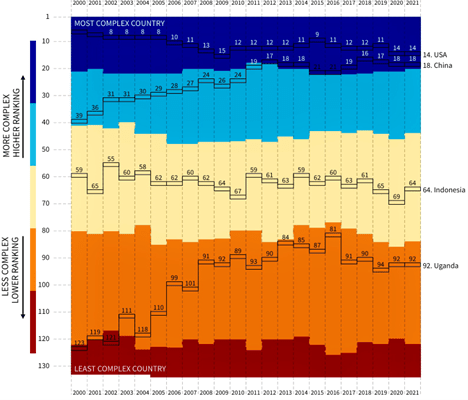

King claims that productive knowledge is totally monopolized by the G7 countries, and especially by the USA. But the prestigious Harvard Growth Lab paints quite a different picture. The Harvard Growth Lab’s Country Rankings assess the current state of a country’s productive knowledge, through an index of Economic Complexity (ECI). “Economic development requires the accumulation of productive knowledge and its use in both more and more complex industries. Countries improve their ECI by increasing the number and complexity of the products they successfully export”.

How does China rank? The US ranks #14 and China now ranks just behind with an ECI of 18. More significantly, China has jumped from 39th in 2000 to 18th by 2021; the US has fallen from 8th to 14th in that span.

An export platform for low value goods?

Seen from the outside, Chinese exports appear to be a really big deal, amounting to 15% of the world total. And that share has been rising since China has been growing so fast. But compared to the Chinese economy, they are surprisingly unimportant. Quite simply, China’s production is growing faster than its exports – even though both are growing at breakneck speed. I say ‘surprisingly’ since the actual number, 7%, is smaller than I think many would have guessed.6

China’s rising share of world exports is not an indicator of excessive reliance on foreign trade. But It does show that Chinese manufacturers remain competitive in world markets, despite the efforts by the US to sabotage its economy with tariffs and other protectionist measures like the CHIPS Act. This export success does not mean that China depends on exports for its growth. China is growing mainly because of production for the home economy .

Due to its recent focus on infrastructure development, industrial expansion, and technological advancements China’s investment to GDP ratio (fixed capital relative to total output) is now higher than that of the the G7 countries. The government has implemented policies to encourage investment in various sectors of the economy, leading to a higher overall investment-to-GDP ratio. While Western critics see this as a sign of “excessive savings” China’s economy has grown more than four times faster than the consumer-led economies of the G7. Were China to follow the advice of Western critics and reduce investment, downsize its public sector, and “free up” the private sector to increase the supply of consumer goods, the result would certainly be a fall in growth rates even more than they have in recent years.7

China Capitalist?

To see what kind of society China is today we need to consider the class character of the China between 1949, and the turn towards the world market and building capitalism in the late 1970s?

Marxists define the class character of the state in terms of its relationship to the prevailing forms of property in the means of production. King acknowledges that the Chinese revolution ousted parasitic landlordism and freed the country from imperialism. However, “this suggests the greatest success in capitalist development comes through overthrowing capitalism and expelling the imperialists as in China”. And further on he refers to revolutionary China as, “indeed anti-capitalist”. This is more of a description than a clear definition of the specific kind of state the Chinese revolution established. King leaves us wondering exactly what he thinks about this question.

Capitalist or Socialist?

The word socialist is often used as a yardstick for classifying states where capitalism has been overturned. Such states are said to be either socialist or capitalist; either x or not-x; either the one, or the other. Thus Cuba is either socialist or capitalist, and China is either socialist or capitalist, or “state capitalist”.

Why is it important to be clear about the class character of China?

If China is a growing capitalist country rising into the top tier of the 3rd World countries, how did this happen without a violent counterrevolution as in Russia? Was there a qualitative change in the mode of production that brought a Chinese capitalist class to power? Did capitalism evolve from some type of revolutionary anticapitalist state? Can the film of reformism be run backwards so that capitalism grows out of socialism? Marxist theory and the historical record suggest that capitalism can no more evolve gradually from socialism, than socialism grows naturally from capitalism. A change from one form of relations of property in the means of production to another can only come through the replacement of the rule of one class by another.

Transitional States

In The New Economics Preobrazhensky described economically backward countries like the USSR as transitional states halfway between capitalism and socialism. The defining feature of these states is the distribution of the means of production and labor-power according to a conscious plan. As hybrid, transitional modes of production they are marked by the contradiction between two different economic imperatives: one determined by the law of value; the other by the social relations of a planned economy. The law of value distributes resources in accordance with the laws of commodity production. In the era of original accumulation, the socialist state acts to lessen and contain the impact of the law of value; central planning distributes economic resources independently of the market in accordance with socially necessary priorities.

Trotsky saw the USSR as too poor to achieve socialism on its own. Remaining an isolated island in a more advanced capitalist sea, the Soviet workers state degenerated as the state bureaucracy hardened into a privileged bureaucratic caste. However, Trotsky insisted that the revolution survived in the socialized property relations, nationalized industry and central planning. (The Revolution Betrayed)

The New Economics was published in China in 1984, and is read in the economics departments of Chinese universities. Presumably Marxist economists in China are familiar with Preobrazhensky and his theory of primitive socialist accumulation of capital in predominantly agrarian countries. 8

China is in the same category as Russia. Since the revolution of 1949 it has been thoroughly transformed by overturning capitalist property relations, replacing the profit system with state control of the commanding heights of industry and agriculture, and coordinating the economy to meet social needs rather than the needs of profit. Like the USSR, China carried the weight of a long history of colonial plunder and landlord pillage. Under the pressure of material scarcity and prolonged isolation the People’s Republic of China was politically deformed from the start by the leadership of an unstable bureaucratic caste embodied in the CCP. Through dictatorial control of the state the nearly 100 million member CCP keeps a tight grip on its monopoly control of investment, employment and production decisions. No matter how powerful the private sector becomes it will remain subject to that control unless its own growth leads to a counterrevolution that restores capitalism.

Under capitalist production the rate of profit on private capital regulates investment cycles and generates periodic economic crises. This is not the case in China. State ownership of the means of production and central planning remain dominant, and the party’s power is firmly rooted there. If production of commodities for profit and the law of value is the motor force of capitalism, then China is non-capitalist. On the other hand it’s not transitioning to socialism which can’t exist confined in a single country and with a powerful private sector.

As a transitional economy operating in the capitalist world market the law of value filters through to the Chinese economy. However, the law is refracted through the prism of the bureaucratic and party apparatus so it does not operate to regulate the Chinese economy. The state sector, operating under a one-party dictatorship, still controls investment, employment and production decisions; the growing capitalist sector is still subject to that control.

By 2003 state owned enterprises (SOEs) accounted for 70% of total fixed assets and 30% of non-agricultural production. The state sector remained dominant in strategic industries, including heavy machinery, steel, petroleum, non-ferrous metals, electricity, telecommunications and transportation. Since the early 2000s the privatization of larger SOEs has virtually ceased. Subsidized by the state banking system just 10% of insolvent SOEs filed for bankruptcy in 2007/2008. The insolvent SOEs were kept afloat by the state banks and local officials concerned about losing access to government resources (Economist, 13 December 2008). By the end of 2016,102 big conglomerates contributed 60% of China’s outbound investments. State-owned enterprises including China General Nuclear Power, and China National Nuclear have assimilated Western technologies and are now engaged in projects in Argentina, Kenya, Pakistan and the UK.

According to the aforementioned Fortune Global 500 list, 25 Chinese companies rank in the top 100. And of these, 21 are state-owned. For the first time China had the largest number of companies represented. 9 Chinese firms slightly outpaced those from the United States- 124 to 121. China now has more firms on the list than France, Germany and Great Britain combined. In the last two decades the number of Chinese firms has grown over twelve fold, while the proportion of American firms has fallen by one-third, from 36% to 25%. 10

If market capitalization serves as a measure of size, the list of the largest state-owned enterprises in China in 2022 shows more than 25 SOEs with a market value of over 100 billion dollars, belonging to industries such as banking, insurance, energy, telecommunications, and transportation. China Telecom is a state-owned enterprise with a market capitalization of $500 billion and is one of the three largest telecommunications companies in China, along with China Mobile and China Unicom. The thirteenth largest is the state owned Bank of China.These Chinese public companies rank among the largest and most influential in the world based on their annual revenue and market capitalization. There are 25 SOEs with a market capitalization over $15.7billion in industries such as banking, insurance, energy, telecommunications, and transportation 11

The largest firms in most industries are SOEs, and 91 of the 124 Chinese members to the latest Fortune Global 500 largest firms are SOEs. These are primarily in the capital-intensive sectors that address public needs, such as utilities, and thus are inevitably less profitable than private companies. 12

Both the size and relative weight of the state sector suggests that despite the inroads of private property, the Chinese economy is still predominantly collectivized. The increasing weight of capitalist enterprises strengthens the forces of counterrevolution, but it does not resolve the fundamental issue of class rule. The task of counterrevolution is the political conquest of state power by the capitalist class. The current signs of growing resistance to further capitalist encroachment by China’s workers and peasants in the form of increased union organizing and mass strike actions over wages and working conditions is evidence that the ultimate fate of the Chinese Revolution has yet to be decided.

The extended tenure of Xi’s rule until 2029 is a major indicator of where China is heading. As the Marxist economist Michael Roberts wrote in 2017:

“What this tells me is that under Xi China will never move towards the dismantling of the party and the state machine in order to develop a ‘bourgeois democracy’ based on a fully market economy and capitalist business. China will remain an economy that is fundamentally state-controlled and directed, with the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy under public ownership and controlled by the party elite.”13

The CCP not only controls the state, it’s embedded in every institution including the private sector. Party cadre are encysted at every level of industry, and party organizations function within virtually every corporation. By controlling the career advancement of senior personnel in all regulatory agencies, all state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and virtually all major financial institutions state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and senior Party positions in all but the smallest non-SOE enterprises, retains sole possession of the economy’s commanding heights. 14

Finance and the monetary system

Banking is controlled by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which is China’s central bank. Additionally, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) oversees and regulates the banking industry to ensure stability and compliance with regulations. Major state-owned banks, such as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), China Construction Bank (CCB), and the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) function in tandem with the central bank.

The Financial Times now complains that China’s bankers, acting in accordance with CCP directives, have been “weighing down the private sector”:

“There are signs that Mr Xi’s strategy to place state-owned companies at the heart of the economy is weighing down the private sector, which has been responsible for such a large part of China’s dynamism over the last four decades. The most striking indication of the choice in favour of state-owned companies has been a ‘stark reversal’ of a decade-long trend of increased bank lending to the private sector… State-owned companies secured 83 per cent of bank loans in 2016, up from 36 per cent in 2010, leading to the ‘crowding out [of] private investment’, he says.”

—Financial Times, 13 May 201915

In an October 2016 speech Xi Jinping was unambiguous: “Party leadership and building the role of the party are the root and soul for state-owned enterprises….The party’s leadership in state-owned enterprises is a major political principle, and that principle must be insisted on.” CCP patronage has long insulated SOEs from many of the central concerns of private enterprises, like turning a profit or repaying loans.

“The Party tells the banks to loan to the SOEs, but it seems unable to tell the SOEs to repay the loans. This gets at the nub of the issue: the Party wants the banks to support the SOEs in all circumstances. If the SOEs fail to repay, the Party won’t blame bank management for losing money; it will only blame bankers for not doing what they are told. Simply reforming the banks cannot change SOE behavior or that of the Party itself.” (Red Capitalism. Carl E. Walter, Fraser J. T. Howie 2012)16

When China relaxed its capital controls the economy suffered serious capital flight. But 80% of all banks are state-owned with the government directing their lending and deposit policies. There is now no free flow of foreign capital into and out of China. Capital controls are imposed and enforced and the currency’s value is manipulated to set economic targets much to the annoyance of US finance capital.

“China’s financial system, which is dominated by four big state-owned banks, does not operate like those in capitalist countries. Chinese bankers do not invest in companies likely to generate the highest returns—if they did, private enterprises would get most of the money. Instead they issue credit in accordance with priorities set by the CCP. 17

Stock exchanges

Which enterprises may be listed on the stock exchanges is strictly controlled by the state. As of 2021, approximately 70% of firms listed on the Chinese stock exchanges were state-owned enterprises. These state-owned enterprises play a significant role in China’s economy and stock market. Share markets don’t operate like the stock markets of finance capitalism. Chinese enterprises raise capital mostly through the nationalized banking system, not by floating new stock through investment banks. Less than 8% of the population operates in the stock market as “retail investors” as opposed to institutional investors. Trading shares on the Chinese casino stock markets is basically like betting on a horse; or better, it’s like putting money on one’s favorite SOE.

The qualitative questions

As Chinese economist Dic Lo asks :

“How can it be possible, in our times, for a late-developing nation to move up the world political-economic hierarchy to become imperialist? Can anyone on the left answer this question?”

“How do we explain China’s success in raising 850m of poverty, and reaching such phenomenal growth on a capitalist basis? According to World Bank figures, a disproportionate share of this change has occurred over the last twenty years. How can a ‘capitalist’ economy have bucked the trend, when the record of all other capitalist economies can show no such result? How is this exception possible if China is just another capitalist economy entangled in the same web of global market relations as the dominant capitalist powers? According to Dic Lo, the accumulation of capital by the state sector has been the major engine of growth:

“How do we explain that while the capitalist economies have remained mired in a slump since the 2008 GFM, the Chinese economy has continued steady growth, reaching national output second only to the US?” 18

Though Chinese growth has fallen since 2008, it has remained high in comparison to the stagnant capitalist countries. China’s years of peak highs doubled real living standards every 13 years; and its poverty rate fell from 88% in 1981 to 0.7% in 2015 as measured by the % of people living on the equivalent of US $1.90 or less per day. While the world capitalist economies remain mired in a deep slump since the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese economy has continued robust growth reaching national output second only to the US.

No slumps

China has not had a contraction in national income in any year since 1976, while the consumer-led G7 economies have had slumps in 1980-2, 1991, 2001, 2008-9 and 2020. Much has been made of China’s ‘disastrous’ zero COVID policy. China’s Zero COVID policy not only saved millions of lives but its economy didn’t slide into a slump in 2020 like all the G7 capitalist economies.

The COVID stress test

As the Bolshevik Tendency points out, “Workers in the US and other imperialist countries were forced back to work without adequate health and safety provisions in the interests of capitalist profitability. By contrast, Beijing forced private companies to immediately begin producing goods necessary to contain the virus.”

When China imposed a stringent lock down in the Spring of 2020 its economic activity fell by a whopping 25%. By building specialized hospitals to quarantine the infected, rushing medical teams from all China to Wuhan, the rigorous application of well known public health infection control policies, and rapid development of a vaccine, the economy was able to safely reopen by summer 2020. As early as December 2020, the state-owned company Sinopharm developed a vaccine (BBIBP-CorV). Another Chinese firm, Sinovac Biotech, developed CoronaVac. Unlike the imperialist countries where the vaccines were hoarded, China distributed its vaccines around the world pursuing “vaccine diplomacy” and multilateral partnerships as part of a coordinated effort to combat the global pandemic. As of today (2024), while the US has recorded 3600 deaths per million from the virus, China has lost just 4 per million.

Central planning

The Chinese economy is not a purely centrally planned economy (neither was the USSR in the 20s during the NEP), but neither is it a fully market-based economy. The hybrid system combines elements of both planning and market mechanisms, with varying degrees of state intervention and market liberalization. 19

According to Xi, and the CCP, the Chinese economy can be characterized as “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” which means that the state still owns and controls the strategic sectors of the economy, such as banking, energy, telecommunications, and transportation, while allowing private enterprises to compete in other sectors, such as manufacturing, services, and agriculture. 20

Uneven and combined development

Under globalized production the backward and more advanced countries are now so interwoven that depending on the economic and cultural capacities of a country, backwardness can actually confer “a privilege.” The privilege lies in the possibility that a dominated country, under certain conditions, can quickly assimilate the more advanced technologies of the imperialist country. Russia in 1917 was the classic example of this; and even more favorable conditions exist in China today.

A key driver of China’s growth has been the transformation and reshaping of the Chinese working class. In the course of a generation, several hundred million former peasants have become urban workers, mostly in cities that grew up overnight. These migrants from the countryside were a seemingly bottomless well of labor for the exporting factories that have made China the new “workshop of the world.” Shenzhen is emblematic of this class transformation, having grown from a population of some 30,000 in 1980 to over eight million by 2000; and from 8 million to 18 million by 2020. The flow of migrant labor pouring into the industrial cities from all China has economically completed the unification of the country begun in 1949. With 125 million workers China now has the largest proletariat in the world. And it is far from passive.

In an interview with the South China Morning Post in 2016, Geoffrey Crothall of the China Labour Bulletin was asked, “Why are we seeing an increased number of strikes and worker protests in China?” His answer is worth quoting at some length:

“One of the key reasons is simply that strikes are much more visible. Just about every factory worker, especially in Guangdong, has a cheap smartphone and can post news about their strike and the response of management and the local government to it on social media and have that information circulate within a matter of minutes. This enhanced visibility has also encouraged more workers to take strike action. They see workers from other factories or workplaces that are in exactly the same position as them taking strike action and they think, “We can do this too.”

Striking Workers in Guangdong, just a generation removed from rural poverty, using cell phones and social media to spread their strike is a graphic example of the law of uneven and combined development.

Another example of the operation of combined development, and of the importance of getting the noncapitalist character of China right, is clearly shown by the case of Huawei’s launch of the 5G Mate60 Pro in September 2023.

Huawei was believed crippled by the US ban on the sale to China of semiconductor chips as well as the chip engraving technology needed to make high speed 5G smartphones. The sanctions were designed to put Huawei 14 years behind world leader Apple. Huawei’s Taiwanese supplier (TSMC) couldn’t sell its chips to Chinese firms. The Dutch firm ASLM, the only company in the world making advanced chip engraving technology for nanometer scale chips, was banned from selling its most advanced EUV machine to China.

“In August 2023, Huawei unveiled a new smartphone with 5G capabilities and a cutting-edge processor. A teardown of the Mate 60 Pro by TechInsights for Bloomberg News revealed the chip powering the device was produced by China’s Semiconductor Manufacturing Integrated China (SMIC). This raised questions about SMIC’s capabilities and the effectiveness of US-led controls. (The story can be viewed here: )

Enter the State Owned Enterprises

While SMIC isn’t a fully state-owned enterprise it has close ties with the Chinese government and receives significant state subsidies and support. SMIC’s largest shareholder happens to be China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund Co., Ltd. (CICIIF). CICIF is a state-backed fund founded to promote the development of China’s semiconductor industry.

CICIIF owns 15% of SMIC’s shares. Other major shareholders are Datang Telecom Technology, an SOE that provides telecommunications equipment and services, and Shanghai Industrial Investment (Holdings), another state-owned investment company. Together, these three shareholders control 36.32% of SMIC’s shares.21

But ASML was able sell its older generation DUV engraver to China because it wasn’t thought capable of handling these micro nanochips. Somehow China rapidly retrofitted the DUV technology to squeeze a 7nm chip into the phone.

This breakthrough left western pundits and the US political class in Washington scratching its collective head. Can it be seriously argued that this leap would have been possible without the Chinese SOEs and the state stepping in to coordinate it? The facts speak for themselves.

In his own examination of the Huawei case King failed to foresee this eventuality. Worse still he claimed it wasn’t possible. In his “original elaboration” of Lenin there is no place for a tech firm in “capitalist China” outc ompeting its imperialist rivals in the monopoly capitalist sector. Short of a world socialist revolution, China must remain trapped in the low end/low skill commodity exporting sector with no chance for real development. But what if China was non-capitalist?

King counters the popular theory of a multipolar world order of the BRICS bloc of countries led by “Rising China” emerging to displace the US dominated unipolar order. On the other hand, King paints a picture of a rigidly bipolar world, where all the polarities lie along a single axis: the monopoly/non-monopoly; the imperialist countries/dominated countries; the high value monopoly capital/low value non-monopoly capital; the high tech knowledge countries/low tech knowledge countries. Just as there are negative and positive electric charges there are monopoly and non-monopoly countries. There’s no other possibility in King’s model.

This is a picture of a world frozen since Lenin wrote Imperialism in 1916. The most change possible in the global labor process is for a non-monopoly country like China to reach the highest rung of the poor countries and become the wealthiest of the poorest. And this ascent only comes from a competitive advantage giving China a larger share of the mass of surplus value allocated to that sector as a whole. So a relatively advantaged 3rd World country takes a bigger slice of the total global wealth pie. A non-monopoly country can’t advance at the expense of a monopoly country. China’s gain can come only at the expense of the rest of the non-monopoly world.

On this point Ernest Mandel’s words deserve quoting:

“Lenin’s remarks on the tendency of monopoly capitalism to arrest technical progress should be slightly modified. It is true that the monopolies strive to monopolize research and suppress or retard the application of many technical discoveries; but it is equally true that monopoly capitalism also calls forth an increase in these technical discoveries. One reason for this is the monopolies themselves need to open new sectors of exploitation in order to have an outlet for their excess capital.” 22

Lenin’s theory of imperialism was based on analyzing the structure of the modern capitalist firm, not on Marx’s theory of value. His focus on the transition from an era of competitive capitalism to one of monopoly, identified the central defining change in capitalism. This was a major advance in seeing imperialism as expansion outwards accompanied by internal decay. However, while Lenin’s Imperialism provides an excellent description of its features, a list of traits is not a unified theory. In terms of Marx’s theory of value, what caused capitalism to decay to the point where it no longer develops the productive forces and becomes a parasite on them?

In his “The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System” (1929) Henryk Grossman expanded on Lenin by focusing on the internal dynamics of capitalism that lead it to instability and periodic crises.

When Marx wrote “The real barrier of capitalist production is capital itself” (Capital Vol. III Part III Ch 15) he was referring to an inherent contradiction within the capitalist system. Marx argued that the relentless pursuit of increased profits and the unending accumulation of capital would eventually run up against its own limitations and contradictions. As capital accumulation increases, the organic composition of capital will eventually exceed the expansion of surplus value needed to satisfy monopoly capital’s need for adequate rates of profit. In response to the falling rate of profit, monopoly capital exports more capital to earn higher rates of profit by exploiting the cheaper labor and resources of the less developed countries. The unequal exchange of value in foreign trade, monopoly profits, and the export of capital are all ways that capitalism circumvents its profitability crisis. The crux is that export of capital, technology transfer, and industrial relocation from the advanced imperialist countries to the dominated ones is driven by declining profitability at home. The protracted transfer and relocation of capital is bound to create new productive capacity in the recipient economies. The evidence suggests that this is the case for China today.

What’s In a Name?

Is the debate over China just hairsplitting? What difference does it make if we view China as capitalist, socialist, state capitalist, or a transitional formation? In the event of military conflict won’t Marxists defend China against imperialism on principle? Can those who view China as a predatory imperialist power be expected to defend it in a conflict with the U.S.? How can a movement against the war be organized when both sides are imperialist gangsters? We are more likely to see them supporting “pro-democracy” forces like the much ballyhooed oppression of the Uigher people or Tibetans that the western media thunders on about. During the imperialist war on Vietnam we heard “Neither Moscow nor Washington” from the “3rd Camp” state capitalist pseudo-Trotskyists. Will we soon hear the slogan,“Neither Beijing nor Washington”?

As the US/China conflict intensifies it makes a big difference if China is just the newest bully on the capitalist block. As non-capitalist China increases its production of media and other high value-added industries i.e. semiconductor chip design and production, cell phones, robotic machine tools, medical devices, AI and optics, it is entering the terrain of direct competition with major US-based companies.

Should China be perceived as blocking further penetration by US capital, and moving out of its assigned lane in the global division of labor to undercut US markets, the conflict will not be between two competing capitalist powers. In the context of the long-term decline of American capitalism, China faces the prospect of war with the US in the next decade.

The ‘rise’ of China is not primarily the result of its military strength. It reflects importantly a declining American competitive position, expressed by obsolescent infrastructure, inadequate attention to research and development and a seemingly dysfunctional governmental process.” (On China, 2011 Henry Kissinger)

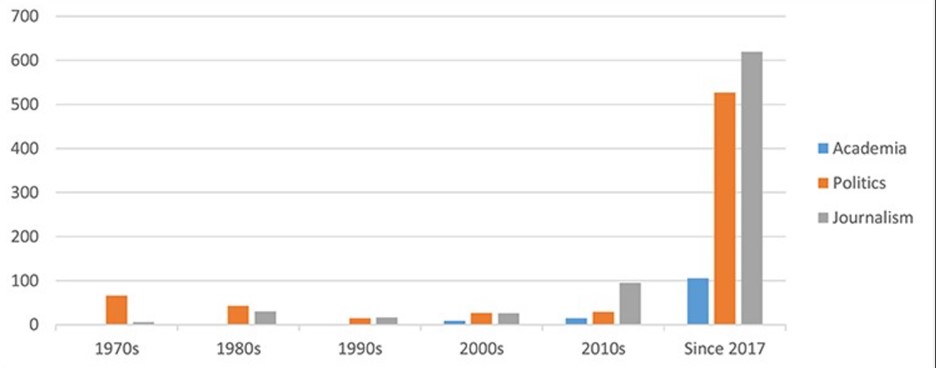

After 2017 when the US National Security Council named China along with Russia as “strategic competitors” the terminology became ubiquitous. See graph below of the number of documents referencing “Strategic Competition” across discourses” since 2017.

There are many reasons why most Marxists think China is capitalist. With more than 1,000 billionaires it’s the country with the second-highest number in the world after the United States (though the concentration of billionaires in the US is ~ 5x that of China). China has a higher level of income inequality compared to the United States (Gini index, China is ~46.7; for the US it is ~41.5). There’s a large wealth gap between the urban and rural populations, between the party leaders and the cadres, between Hong Kong and other Chinese cities. This is not the image of a socialist country.

However, China is not a socialist society but a transitional formation; a contradictory hybrid, as previously described. While it may not be transitioning to socialism it has not yet witnessed the overturn of the fundamental gains of the Chinese revolution. The main issue facing China is which half of the hybrid will prevail in the long run. Will the private sector grow to override the public sector? Will the law of value and profitability override the planned economy?

Even in cases when a transitional state is as deformed, misshapen and ugly on its surface as China appears, “It is the duty of revolutionists to defend tooth and nail every position gained by the working class, whether it involves democratic rights, wages scales, or so colossal a conquest of mankind as the nationalization of the means of production and planned economy.” Leon Trotsky

Footnotes

- Through Pluripolarity to Socialism: A Manifesto International Manifesto Group September 2021 ↩︎

- (Foster, J.B. Review of China’s economic dialectic: The original aspiration of reform. [Cheng, E.]. Belt & Road Initiative Quarterly, 3(2), 76-77.) ↩︎

- Why the China-U.S. rivalry is at a crucial turning point—and what it means for business ↩︎

- 15 Biggest Chinese State-Owned Companies ↩︎

- What Do China’s High Patent Numbers Really Mean?

↩︎ - Fact Checking Rana Foroohar’s OpEd Piece in the FT

↩︎ - Fact Checking Rana Foroohar’s OpEd Piece in the FT ↩︎

- China: Capitalist, Socialist, or “Weird Beast”? ↩︎

- Why the China-U.S. rivalry is at a crucial turning point—and what it means for business ↩︎

- 15 Biggest Chinese State Owned Companies ↩︎

- Market capitalization of the largest listed state-owned enterprises in China in 2022 ↩︎

- The Biggest But Not the Strongest: China’s Place in the Fortune Global 500 ↩︎

- Xi takes full control of China’s future ↩︎

- Capitalizing China ↩︎

- Xi Jinping’s China: why entrepreneurs feel like second-class citizens ↩︎

- https://search.worldcat.org/search?q=au=%22Howie%2C%20Fraser%20J.%20T.%22 ↩︎

- The Myth of Capitalist China ‘Trotskyist’ impressionists can’t explain resurgent state sector ↩︎

- As cited in Michael Roberts China workshop: challenging the misconceptions ↩︎

- China’s economic collapse carries a warning about our own future ↩︎

- https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/abstract/document/obo-9780199756223/obo-9780199756223-0225.xml/ ↩︎

- ROGERS, MCCAUL, COLLEAGUES URGE ACTION AGAINST HUAWEI AND SMIC ↩︎

- The Marxist Theory of Imperialism and its Critics ↩︎

Hi Robert

Thanks for the review.

You argue that Chinese production of 7nm Chips disproves my contention that China cannot catch up to the imperialist core’s productive dominance. But the most advanced chips are now 3nm. So how does a 7nm chip (produced using imported second tier machines) prove your point? And even if China could equal, at least for a time, imperialist productive capacity in ONE leading area, that would still not disprove the massive discrepancy across the societies as a whole – though it appears to have not done that yet. If that is wrong, how do you explain the fact China remains poor compared to the US and Australia? Surely if the biggest nation in the world was also leading the technologically it would also be dominant economically – or at least starting to be. That is not happening.

LikeLike

Hi Sam,

Thanks for your comments. I agree that China is not economically “catching up” to the US. But I disagree with you on the limits to China’s growth horizon. The Huawei case is just one example of its ability to mobilize public and private resources needed to break the technology blockade. The engraving machine that China “borrowed” as you write, leaked through the sanctions regime because it was unable to engrave chips smaller than 14nm. Chinese engineers retrofitted it to produce the 7nm Huawei Mate60 Pro which is now rated the number one smartphone. ( https://web.archive.org/web/20240105195617/https://www.dxomark.com/smartphones/Huawei/Mate-60-Pro+)

The recent data on new invention patent filings, China’s rapid rise in the economic complexity index of productive knowledge, the outpacing of US firms on the Global Fortune 500 rankings, and the pace of advanced R & D in high value added cutting edge technology make a compelling case that China has transitioned from a backward export platform for low value manufactures to the global North. At least as seen from the US, China presents an economic threat to its declining hegemony.

I urged readers to buy the book on its great strengths; and that’s the response I’m seeing on social media.

Comradely,

Robert Montgomery

LikeLike

[…] classconscious.org is republishing this interview published on Workers World website (workers.org) on June 29th 2024. We believe it is an excellent interview that aligns with our view that China retains the key elements of a workers state despite the large capitalist presence. This analysis has been outlined by Robert Montgomery in his 2019 article “China: Capitalist, Socialist, or “Weird Beast”?” and more recently in his article “Imperialism and the Development Myth”: An important defence of Lenin but is Chinese development rea… “ […]

LikeLike