by Robert Montgomery, January 17th 2024

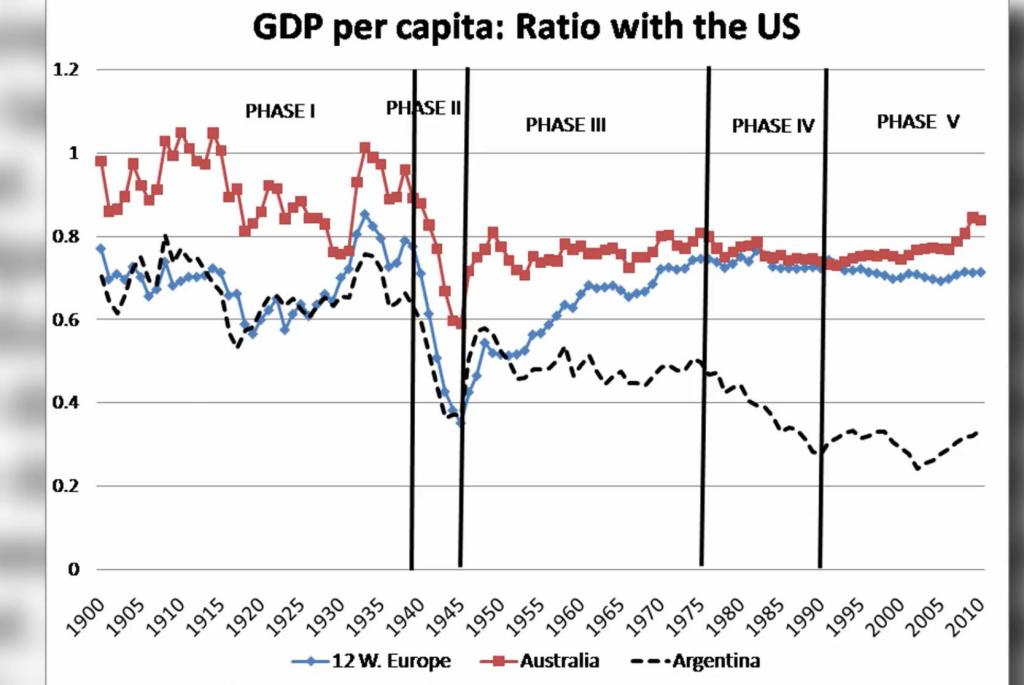

The election of the clownish proto-fascist Milei in November 2023 is just the latest manifestation of the class war in Argentina and another effort by the ruling class to protect and deepen the neo-liberal exploitation of the workers. In 2023, Argentina celebrated the 40th anniversary of reclaiming democracy after the oppressive “Dirty War” dictatorship. While political democracy was reinstated in December 1983, over the past 50 years the neoliberal economic changes introduced by the dictatorship have solidified. Argentina has undergone a prolonged process of deindustrialization since the 1976 coup. Neoliberalism took root in the 1976 dictatorship, intensified in the 1990s under the Menem administration, culminating in the 2001 financial collapse. The subsequent decade of Kirchnerist stabilization ended in the bust of 2014. Macri’s debt-driven hyperinflation paved the way for the proto-fascist Milei elected in November.

As Marxist economist Michael Roberts writes:

“Peronism has failed to deliver on economic expansion, a stable currency and low inflation. But it has also failed to deliver on ending poverty and reducing inequality. Argentina’s official poverty rate rose to 40.1% in the first half of 2023. According to the World Inequality Database, the top 1% have 26% of net personal wealth, the top 10% have 59%, while the bottom 50% have just 5%. In incomes, the top 1% have 15%, the top 10%, 47% and the bottom 50%, just 14%.”

The protracted decline saw the continued implementation of unsuccessful neoliberal policies overseen by the IMF. The neoliberal deindustrialization of Argentina was driven by the export of surplus value to the centers of imperialist finance capital in the Global North.

From 1975 to 1990, real per capita income plummeted by over 20%, erasing three decades of economic progress. The once-thriving manufacturing industry which had grown until the mid-1970s, entered a sustained decline. By the early 1990s, the level of industrialization mirrored that of the 1940s.

How was it possible for Argentina to go from being the most developed country in Latin America to the total collapse of 2001 which threw over half its population into poverty? The answer requires an overview of the 3/4ths century of economic development in Argentina from 1an industrializing country to the financialized zombie state of the present. To understand the roots of the longterm crisis it’s necessary to review the underlying shifts in the political economy of Argentina that led to deindustrialization, an astronomical increase in foreign debt, hyperinflation of 140%, and an overall fall in the living standards of the majority of its people.

The Peron Era

From 1930 to 1976, Argentina pursued an import substitution industrialization (ISI) economic strategy. ISI involved state measures like tariffs and investment regulations to shield emerging industries, fostering diversification into both light and heavy manufacturing. Instead of functioning as an export conduit for agricultural products to the Global North, Argentina prioritized the development of its domestic manufacturing. The country transitioned from a semi-colonial to a dependent capitalist status, exemplified by its move away from British economic dominance, where railways and ports, predominantly controlled by British capital, primarily served as export channels for the limited landed oligarchy’s beef and grain estates. Argentina was subject to total trade control by Britain.

During WWII the disruption of global supply chains provided an opportunity for a nationalist faction in the military led by Juan Peron to implement state-driven measures. These measures included import substitution, state monopoly on primary exports, tariffs, and other interventions, aiming to diversify the economy into both light and heavy manufacturing instead of merely exporting agricultural products. Argentina emerged as a model for transitioning from a semi-colonial status to that of a bourgeois nation state. The state’s monopoly on foreign trade in grain and beef acted as a rent on the export sector, supporting domestic manufacturing through subsidies. Previously, Argentina had mainly served as an export channel to Britain for beef and grain from the rural estates of a small landed oligarchy. Between 1946 and 1948, nationalization of French and British-owned railways occurred, and transport networks expanded, reaching 120,000 kilometers (72,000 miles) by 1954. Protectionist policies and increased government credits, funded by progressive taxes on traditional landed elites, propelled substantial growth of the internal market (i. e.) radio sales increased 600% and fridge sales grew 218%, among others. By the 1950s the country was no longer a semi-colony but had transitioned to a dependent but still backward bourgeois nation with a growing industrial base, urbanization, increased consumption, social welfare services, and a growing proletariat. N.b.

A dependent country exports commodities but not capital. Most importantly, a dependent country is a net exporter of surplus value to the dominant capitalist countries. As long as it remains capitalist it won’t see real economic development with rising living standards for the masses. Such a level of economic development requires a sufficiently high level of the productivity of labor to allow it to compete with the dominant centers of the capitalist world system. Because of its belated capitalist development, a dependent country remains oppressed by imperialism. Since a dependent country exports commodities, the unequal exchange of value on the world market transfers surplus value to the dominant imperialist countries. As long as it remains trapped in the world capitalist market a dependent country will remain economically backward and exploited by the technologically more advanced industrial sectors. Breaking the chains of dependency requires the development of a level of labor productivity needed to compete on the world market with the dominant capitalist powers. This would require a revolutionary transfer of power to the working class majority which produces the surplus value, to begin the transition to economic planning based on social needs rather than private profit.

From the mid-1960s, Argentina experienced the growth of its manufacturing industry. By 1973 exports accounted for over two thirds of all exports. But under the dictatorship’s neoliberal restructuring the balance of trade and payments deteriorated. Argentina experienced chronic trade deficits with the value of its imports exceeding that of its exports. This was primarily due to the gutting of domestic industry and the subsequent inability to compete in the global export markets. The government had to borrow heavily to finance its imports and the country’s external debt increased significantly. The mounting external debt owed foreign creditors contributed to a deteriorating balance of payments, as the country struggled to make its debt service payments and cover its import expenses. The economic downturn and worsening balance of trade and payments during the dictatorship of 1976 to 1983 were major factors contributing to the subsequent economic crisis in Argentina in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Years of struggle: The 1960’s

Just as the Cuban revolution set all Latin America afire with a spirit of anti-imperialism and social revolution, it animated Argentinian youth with the possibility of revolutionary change. In 1968 Che Guevara, a native son of Argentina, had given his own life fighting to spread the revolution to Bolivia. In 1970 the Unidad Popular coalition was elected in Chile promising a transition to socialism.

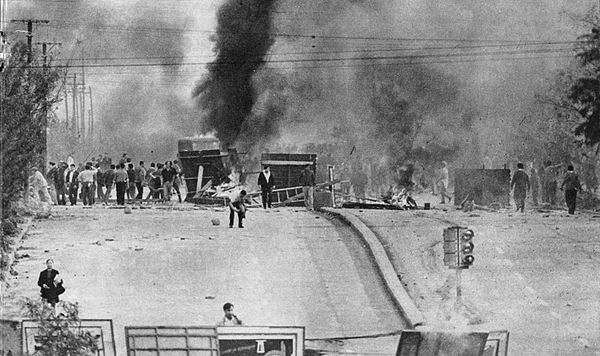

In 1969 militant Argentinian workers and youth rose together in a mass insurrection against the Onganía dictatorship. The Cordobazo brought student youth and workers together in joint struggle against the military government. In Rosario and Tucuman mass strikes exploded. In industrial Córdoba workers took control of the city, setting up defensive barricades, burning administrative centers, and the headquarters of the foreign firms, Citroen and Xerox. The leaders of CGT union federation called for a National strike on the day after the general strike in Córdoba. Sugar mill workers in Tucumán took over their factory, holding the manager hostage in return for unpaid wages.

The Cordobazo was something new and different. It was not just an economic strike, it was political one as well. For the 1st time radical youth and the workers locked arms together in joint struggle against a military government. Bringing down a dictatorship by mass industrial uprisings led the radical youth to conclude that revolutionary armed struggle could win popular support in the urban centers. Several Guevarist urban guerrilla groups formed after the Cordobazo. The largest were the Revolutionary Peronists (Monteneros) and the Trotskyist/Maoist Peoples Revolutionary Army (ERP). The emergence of the revolutionary left wing Monteneros threatened the control of the CGT union bureaucracy over the Peronist movement, and the two factions battled each other savagely for leadership.

Peron Returns

Hector Campora running as a placeholder for Peron himself was elected president in May 1973. Campora took office in the presence of Chilean President Allende and Cuban President Dorticos as one million people acclaimed the new president on the Plaza de Mayo. in the following months social ferment exploded as approximatively 600 strikes and factory occupations took place. The revolutionary left suspended the armed struggle to participate in the democratization process. This leftward motion alarmed the Peronist right-wing trade union bureaucracy, so to unify the fractured movement and control the economic crisis, Perón was recalled from Spain.

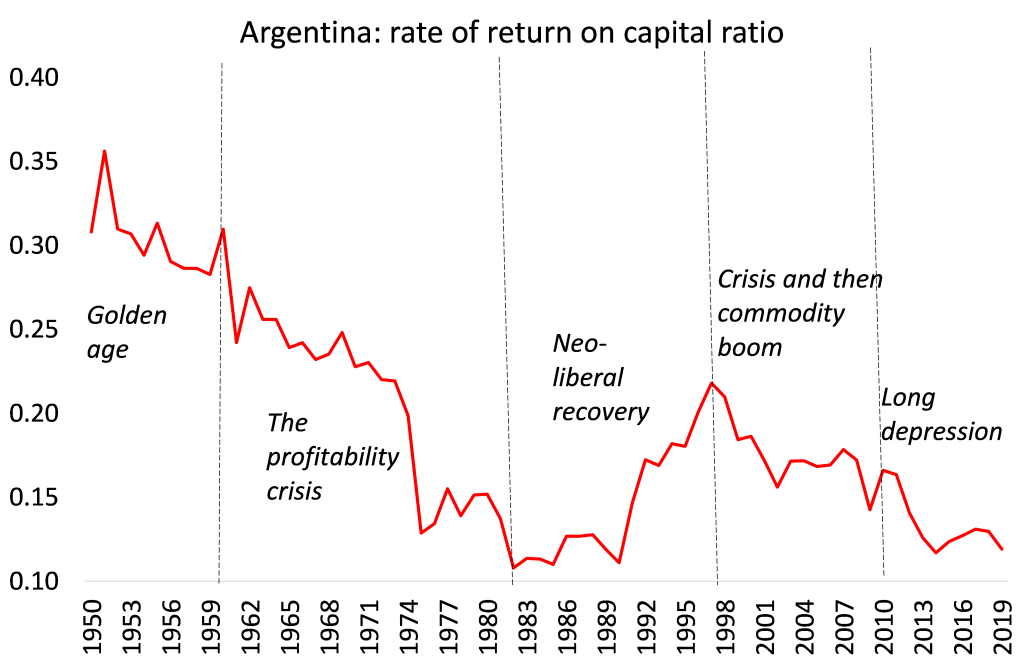

As he struggled to balance between his own left and right, Peron’s economic policies drove inflation into triple digits. Prior to Peron’s return the rate of profit had been steadily falling for five years. In the context of a crisis of capitalist profitability, Keynesian style state spending and the welfare state policies of the past failed to slow the economic crisis. When his right wing supporters attacked the left-wing youth the strategy began to backfire. Peron expelled the Monteneros from the movement they began armed struggle against the conservative CGT union bureaucracy. The intra-Peronist vendetta played into the hands of Peron’s personal secretary López Riga, the founder of the paramilitary death squads of the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance (the AAA).

After Peron’s death in 1974 his wife Isabel continued his social and economic policies. In 1975 the peso was devalued by 50% causing massive economic havoc, inflation, loss of savings, and hardship for the middle and lower classes, especially for public employees and retirees. Isabel Peron turned to the IMF hoping for a loan of 800 million dollars to stabilize the economy. The IMF turned down her request.

Between deepening recession, consumer price inflation, unemployment, and the terror of Lopez Riga’s ‘AAA’ death squads, public dissatisfaction set the stage for the Isabel Peron’s fall. When the military junta seized control in 1976 there was no resistance . The day after the junta took over the IMF loaned the Vidal government $1.3 billion.

The Junta enters

When the military junta seized power in March 1976, the new government shifted away from the state driven policies of Peronism. The junta had two main objectives:

- Repression of the left and the working class which reflected the junta’s obsession with crushing all dissent, especially among the radical youth and the organized working class. In 1979 General Videla stated, “We have taken 30,000 subversives and another 20,000 are missing.” He was referring to the estimated number of people who were forcibly disappeared, tortured, and killed during the dictatorship’s “Dirty War.”A significant portion of these victims were political dissidents, human rights activists, unionists, and suspected left-wing militants. The “Dirty War” aimed to suppress opposition and consolidate control through systematic violence and state terrorism.

- Restructuring the structure of capital accumulation by:

- reducing working class wages and its share in the distribution of the national income

- opening up the economy to foreign direct investment

- deregulating markets and drastically reducing state intervention in the economy

- strengthening the financial sector and ending the central role of manufacturing industry in the country’s economy.

The neoliberal “shock therapy” was the same as that imposed on Chile by the Pinochet dictatorship, and was even managed by the same students of free market monetarist, Milton Friedman. The central bank was directed by Adolfo Diz one of the so called “Chicago Boys.” It was Diz who implemented much of De Hoz’s program. All checks and controls on banks were eliminated; toxic bank loans were assumed by the government which took responsibility for their debts. At the same time credit to domestic industries was squeezed. The government nationalization of bank debts was the start of the sovereign debt crisis plaguing Argentina today. In 1979 de Hoz went so far as to cede legal jurisdiction over Argentina’s sovereign debt from Buenos Aires to NYC!

As real wages lost 40% of their purchasing power, consumer spending fell reducing the demand for domestically made goods. Falling demand combined with the cheaper foreign imports to further sap the profits of Argentine manufacturers. The rate of real investment declined as the profit rate of Argentine manufacturing continued to fall, and inflation soared again.

The dictatorship carried out a program called the Process of National Reorganization (El Proceso de Reorganización Nacional), or simply, “The Process.” It used its power to shift the economy from manufacturing towards agro-export industry. On the one hand it was supportive of the landowning oligarchy; and on the other hand it was antagonistic towards manufacturing bourgeoisie. This shift was reflected in the government’s allying itself more with the Argentinian Rural Society representing the landowning oligarchy, than with the Industrial Union of Argentina which representing the industrialists. The Chicago Boys argued that agricultural rent should no longer be used to subsidize industry as under Peronism, and the high value added exports of the Agro-industry sector should be promoted instead.

The economic and social policies pursued by the military government had the desired effect on Argentinian manufacturing industry. Between 1975 and 1981 manufacturing’s share of the GDP declined from 29 to 22%, industrial employment declined by more than 36%, and industrial production as a whole dropped by 17%. Between 1975 and 1990, real per capita income fell by more than 20%, wiping out almost three decades of economic development. The manufacturing industry, which had experienced a period of uninterrupted growth until the mid-1970s, went into continuous decline. The level of industrialization at the start of the 1990s was similar to that of the 1940s.

There were several main factors contributing to deindustrialization:

- Transnational corporate capital gained a major competitive advantage from Argentina’s concentration on producing primary products while abandoning automobile, steel and heavy manufacturing to cheaper foreign imports, or to local production by the TNCs themselves.

- Liberalization of the economy opened up the national market to penetration by TNCs undercutting domestic producers.

- The junta’s obsession with stamping out dissent, especially among organized workers, was driven by the ghost of the Cordobazo of ‘69. The junta was committed to eliminating the country’s industrial base as the breeding ground of labor unrest.

- Repeated bouts of high inflation made it hard for domestic industry to remain competitive, thus deepening the disinvestment in manufacturing.

Who Rules Argentina?

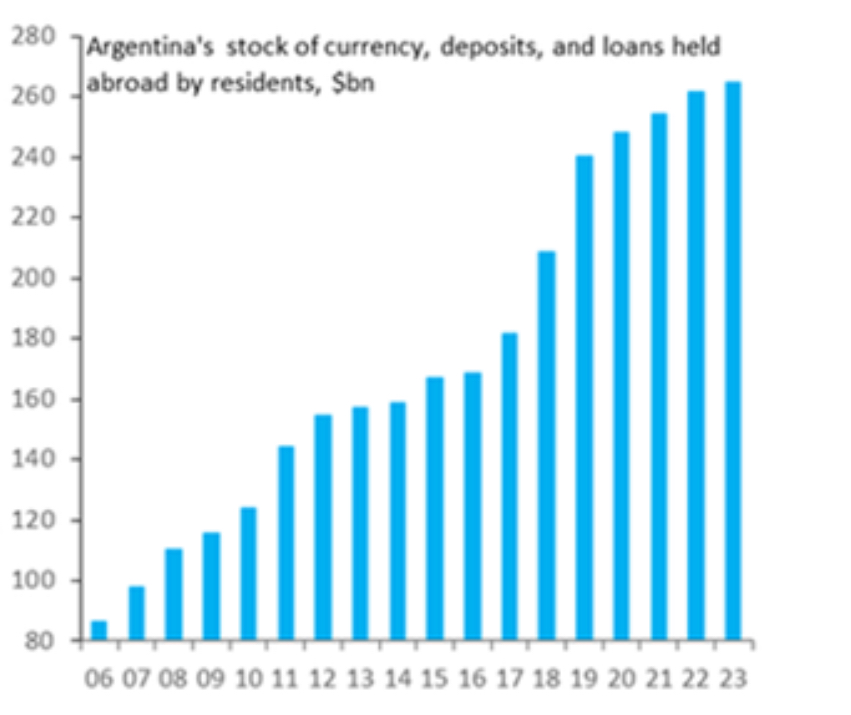

How could deindustrialization be in the interest of the national bourgeoisie? The real burden of deindustrialization fell on the working class, while the industrial bourgeoisie simply shifted much of its investments to finance or withdrew their capital from the country altogether. Nor was the Argentinian bourgeoisie really tethered to the expansion of industrial capital. The dominant fraction of the bourgeoisie invests the bulk of its capital in finance and agro-industry. The neoliberal shift in government economic policy benefited the most powerful companies, such as Bunge & Born, Macri, Perez Company while the less powerful industrial firms were considered expendable.

Some of the most prominent families of the agro-export and financial elite include the:

1. Bemberg: Beef and Cattle

2. Grobocopatel: the “Kings of Soy”

3. Blaquier: cattle ranching and grain production.

4. Chediack: meat processing and grain trading

5. Etchevehere: beef and grain

6. Bunge and Born: transnational company in grains, oilseeds, and sugar.

The class forces behind Milei: Mauricio Macri

Mauricio Macri served as president from 2015-2019, leading the “ala dura” (hard wing) of the Juntos por el Cambio (JxC) coalition. The JxC far right coalition is now the real power standing behind the face of Javier Milei, a libertarian media personality. Milei’s upstart party “La Libertad Avanza” holds only 15% of seats in the lower house and less than 10% of the Senate. To move his austerity legislation through Congress Milei has had to form a coalition with the more powerful parties of the far right. Milei had won the presidency; but Macri had regained political power.

Macri is the heir of the “Grupo Macri” business empire which invests in construction, finance, telecommunications, and real estate. The conglomerate is concentrated in the financial and real estate sector, and operates in the transnational telecom industry. It also owns a major stake in Telecom Argentina. Macri is a major shareholder of Iesca, a construction company involved in major infrastructure projects in Argentina.

Milei

The election of the fascist Milei enjoyed the full support of the Trump faction in the US, the fascist Bolsonaro in Brazil, the Francoite VOX movement in Spain, the IMF and imperialist finance capital, ultra-reactionary billionaire Elon Musk, the NATO stooge Zelensky, the parties of the anti-Peronist right, and a significant mass base in layers of the desperate Argentine middle class.

The mass media’s unrelenting exposure of the theatrical antics of Milei and his manic campaign performances, lent him a populist veneer and publicized the upstart Libertad Avanza party.

Widespread anger existed that the Fernandez government failure to reverse Macri’s program, but ended up applying the same IMF austerity measures. This was a major factor in Milei’s victory. Many traditionally left wing voters disoriented by the Peronist betrayal and confused by Milei’s anti-establishment rhetoric swung behind a campaign directed against “the system of thieves.” So Milei won with 55% of the vote.

In an immediate move towards the dollarization of the economy, Milei devalued the peso by 1/2. The devaluation hammered real wages and savings, making the masses twice as poor as they had been the previous day.

On December 20 Milei announced on national television the “National Emergency Decree.” The omnibus degree demands a severe economic austerity plan in an economy which is already experiencing over 140% inflation and an increase in the poverty rate to almost 50%.

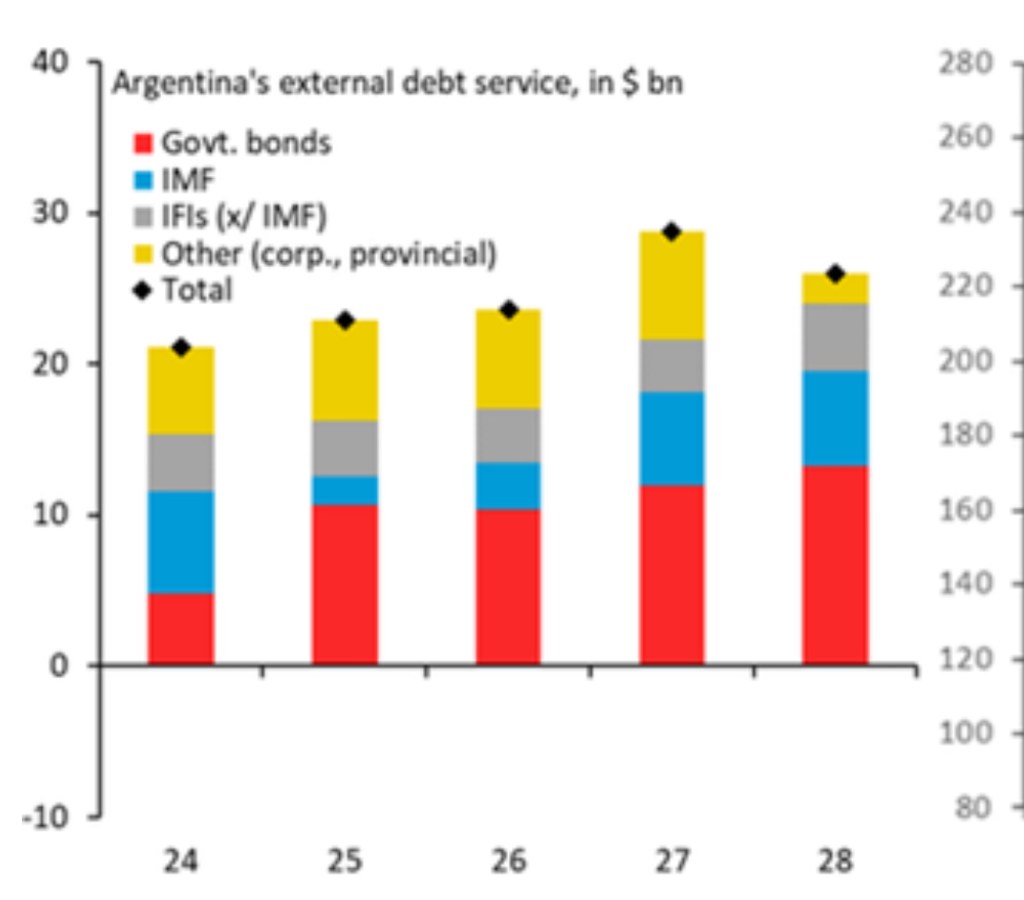

Milei himself says, “things will get worse”. Inflation is predicted to exceed 200% by the end of the year and foreign currency reserves are billions of dollars in deficit. Argentina still owes the IMF and foreign bondholders more than $44 billion from loans agreed by the last right wing government of Macri in the final days of his term in 2019.

Milei is now attacking workers directly by imposing Pinochet “shock treatment” including:

- mass layoffs,

- the privatization of the remaining state owned industry (like the oil and energy company YPG),

- reduction or even the end of the pension system,

- and all the social rights and gains of the working class since the era of Peron.

A lover of the Argentine military dictatorship and Margaret Thatcher, Milei will subject the country to measures typical of brutal austerity in the manner of Pinochet in Chile. These measures will take the current economy from crisis to collapse. The danger looms that the Argentinian ruling elite will resort to military force to crush the inevitable mass resistance that will arise against the misery of the austerity regime. This will require suspending the usual norms of bourgeois democracy to carry out bloody repression of the mass organizations of the working class its social allies. Milei is already moving to overturn the 1983 law in effect since the ouster of the military dictatorship that outlawed the domestic deployment of the armed forces.

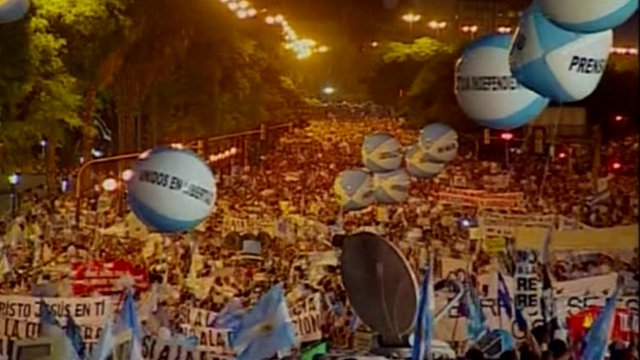

However, what Milei and the Argentinian ruling class would like to do depends on the resistance of the working class. Since December 20th we have already seen mass mobilizations in the streets of the piqueteros, the parties of the left, the cacerlazos banging their pots, and a large march of the CGT unions together with the mass organizations of the left. The CGT has called a general strike for January. And the street mobilizations have spread to the cities of the provinces like Rosario, Cordoba, Tucuman, and Salta in the north.

Peronism gave birth to an organized working class that was classconscious and militant by the 1960s. After nearly a half century of neoliberal restructuring little remains of Argentina’s industrial base or its concentrated proletariat. Argentina is again run by a narrow financial agro-mining elite, and reduced to a niche role in the world market exporting primary products. Buried under a mountain of unpayable IMF debt the days of left nationalist solutions to Argentina’s economic crisis have long since passed. The Peronists and their conservative opponents may well have danced their last tango together.

Yet to announce the final death of Peronism after nearly 80 years of life would be foolish. The banners in the streets say, “Argentina is not for sale!” and the city walls are tagged with, “Milei Traitor”. The pots and pans of the cacerleros sound and the piqueteros are in the streets again. A general strike is looming. Should Melei’s chainsaw fail to force the Argentinian masses to accept the poverty of precariousness and marginalization, we could see Peronism rise again under a left leader like Juan Grabois, the friend of Pope Francisco. But can Peronism in any form move beyond nationalism to embrace a global perspective looking to unite all South America in alliance with the BRICS project of the global South? Would a revitalized Peronism dump its IMF debt and break with the dollar empire? And finally, can Peronism abandon its historic illusions in a cross-class bloc the working masses and the national bourgeoisie?

Sources:

Three to Tango: Argentina, IMF, and Debt

Argentina’s Economic Recovery Policy Choices and Implications

Argentina’s quarter century experiment with neoliberalism: from dictatorship to depression

Argentina’s Economic Recovery: Policy Choices and Implications

State, Market and Neoliberalism in Post-Transition Argentina: The Menem Experiment

Argentina: from Pink Tide to reactionary wave

Democracia, economía y captura del Estado

Argentina: Milei Terminates the contracts of 7,000 State Workers

Argentina’s Debt Battle: Why the ‘Vulture Funds’ are Circling

Milei’s Triumph was a Neatly Planned Media Construction

Michael Roberts: Argentina election: from peso to dollar?

Left Voice: Milei’s Shock Therapy and the Workers’ Response

Left Voice: Tens of Thousands of Argentinians Protest Milei’s Pro-IMF Austerity Plan and Authoritarian Policies